DESIGN DISTRICT

Location: Greenwich Peninsula, London, UK

Client: Knight Dragon

Consultants: Whitby Wood, Skelly & Couch, Artelia, Optimise

[ URBAN DESIGN / INFRASTRUCTURE / EDUCATION / COMMERCE ]

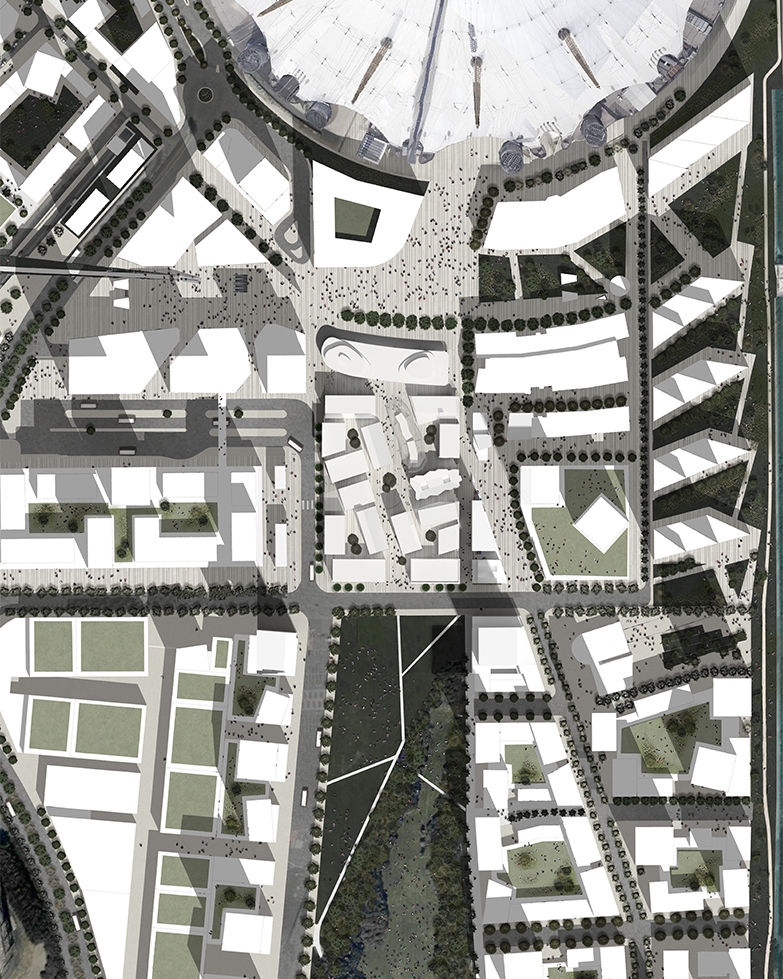

The Design District is part of the Greenwich Peninsula Masterplan and is a vibrant cluster of 16 new buildings for the creative industries at the heart of Greenwich Peninsula. It is designed as a “piece of city”, with a distinctive street grain, architecture, and urban character. The district comprises 16 free-standing buildings composed around five courtyards. Creating 14,000 sqm of studio space for makers in the creative industries.

Having worked on the Greenwich Peninsula Masterplan with Allies and Morrison, HNNA were then directly appointed to concentrate upon the area to the head of the central park and the heart of the peninsula which is known as the Design District. The district comprises 16 free-standing buildings composed around five courtyards. Creating 14,000 sqm of studio space for makers in the creative industries.

In the last half century artists and creatives have been used as a sacrificial catalyst to fuel the gentrification of undesirable, often post-industrial, areas. Once effective they are priced out and lost. The client’s ambition was to produce a permanent location for creative start-ups in the heart of the peninsula to ensure its distinction from other genericized, brand dominated pieces of city. Structures here are low cost in order that tenant rents can be kept affordable - long term - preserving their permanent place in the centre of the peninsula not as a temporary installation or moment but rather as an important cultural component in the urban mix.

As you will see our other work our approach is to resolve the brief not with big architecture but instead create a permeable, accessible urban solution. The most efficient approach would be to produce large, single, sealed industrial scale building with car parking. Particularly given the cost constraints. But we determined to design a “piece of city” not “big architecture”, with a distinctive street grain, architecture, and urban character to create a environment for innovation.

In the wider context of many tall buildings on the Peninsula, the intimate scale of the Design District immediately announces it as a different kind of place.

© HNNA Ltd

Pedestrianised, and comprised of a collection of three-five storey individual buildings, the Design District shares qualities with the scale and tight grain of pre-industrial inner-city neighbourhoods. The height, scale and massing of the buildings is small and human-scale in relation to the tall large footprint masses of surrounding buildings in the overall masterplan. As a plot layout, the scheme sets a strong, clear framework defining all the key spaces, edges, and movement routes.

Despite it’s distinctive urban grain, the scheme meshes with the surrounding masterplan context. The alignment of Chandlers Avenue as it approaches Peninsula Square is one of the principal lines in the Peninsula Masterplan. This alignment is echoed in the primary routes of the Design District, and related sub-geometries pervade the remaining District layout.

These geometries are also enlisted to disrupt otherwise straight axial routes through the District, breaking lines of sight, enhancing the immersive qualities of the Design District’s ‘interior’ courtyards. Entry points to these main routes are flared into open ‘mouths’, most notably to the Gateway Hub, drawing footfall from Peninsula Square to the District Square and thereafter Central Park.

© Knight Dragon Developments Ltd

The buildings are clustered in four groups of four, each cluster enclosing a coworking yard peculiar to its cluster, with a primary shared courtyard in the centre. The front of house District Square is given a more formal orthogonal geometry, establishing its authority. In contrast the back of house coworking yards are irregular and tighter, giving them an attractive informality and inviting interaction between buildings at ground level. All the courtyards are ‘hidden’, being only glimpsed from outside the District, inviting pedestrians to discover each in turn.

All the courtyards are permeable and connect to each other, having routes in and out at every corner. The result provides a sense of spatial containment but not confinement.The proposal of setting a series of buildings and room-like spaces in a network of pedestrian-only lanes defines the urban approach. Unlike a shopping centre or business park, the Design District’s lanes and courtyards are pedestrian, external and shared. It does not have front doors which close, or a roof which contains. It's a place the public can flow through and interact with; a new urban fragment of the city of London. With all the advantages of freedom of movement that being car-free allows.

In addition to its urban, landscape and place-making qualities, the Design District is also an ambitious architectural project in its own right: As discussed the easy route would be a single large industrial building. The decision to split the accommodation into 16 separate buildings was further complicated by the decision to allocate the buildings to 8 different architects.

Our role sitting both sides of the table to oversee the masterplan, coordinate the architects and also be one of them was challenging. The selection of the architects was deliberately undertaken to give a mixed voice. The phrase “Marmite building” was invented and accepted by the client to describe the reality that the different offer of buildings allowed for a range of varied tastes.

At the same time, the physical detachment of each building permits its own distinct architectural language or ‘voice’ particular to that architect. It allows the architect to compose the building form and all external elevations as a coherent sculptural object. This sense of each building achieving a discrete identity is made more complex with each architect designing a pair of buildings.

The pairs are deliberately not adjacent to each other, promoting ‘family’ relationships across the District. The continuity yet diversification of the buildings is deliberate and strategic. Variation and individualisation of building character is encouraged and supported, in a frame. The approach leverages the logic of the contemporary city: heterogeneity of feel, variety of offer, architectural pluralism, and yet cohesiveness in the whole.

We deliberately didn’t set the usual design codes that are typical of masterplans. As part of our urban design, regulatory and economic constraints were well understood.

Budgets were allocated relative to lettable area

In order that the public spaces in the district stay cohesive and the hierarchy of streets remain legible building footprints had to be maintained.

In order that the spaces be affordable for the appropriate users construction costs had to be kept low.

The buildings were allowed play in section as the area required wasn't a maximisation of the footprint extruded to the height constraints.

We also didn’t superimpose a materials palette as we knew that the facade would be a significant proportion of the budget and we were keen architects innovate around the necessary tight cost constraints. The process of design and architectural evolution of the individual buildings followed a dual path. Architects balanced bursts of work in isolation with mutual comparison and response over successive iterations of their designs.

The process of explanation and approval operated very like that of the university crit allowing co-ordination between buildings by mutated association. This offered flexibility to the designs and avoided compromise. As urban designers we saw our role to liberate and enable the creativity of the architect but that wouldn’t have worked without a clear platform.